'King Lear' scene by scene 8

Now a single scene from King Lear for Episode 8, the horrific Act 3 scene 7, in which Gloucester is blinded, and a look at how ‘blindness’ and ‘seeing’ ramify throughout the story.

Also on podcast services like Spotify, Apple and more (search for my name).

You can listen to all 12 episodes here, and also download a free 52-page document with all the transcripts.

TRANSCRIPT

Act 3 scene 7

This is one of the most notorious scenes in all drama. Even in the dry confines of a classroom it makes many pupils squirm in discomfort at the least, perhaps in horror. One professional recording I sometimes use has a squelchy slurpy sound that often makes teenagers cry out in disgust.

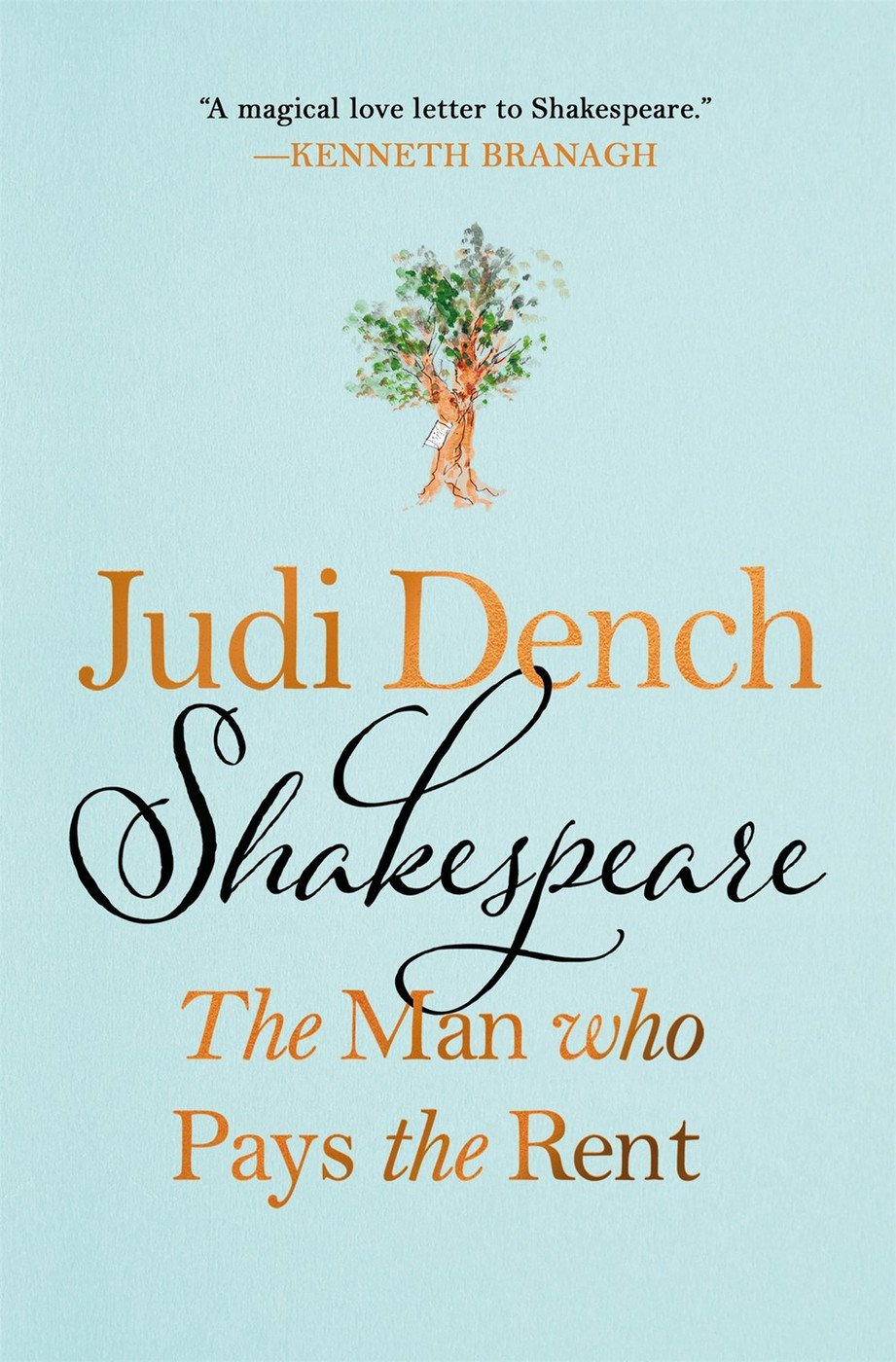

Here’s a brief moment of dark humour before we descend into the grand guignol. In her marvellous recent book, Shakespeare: the man who plays the rent, a series of conversations with Judi Dench, the actor tells the story of a production in which she played Regan. The actor playing Cornwall would come with a lychee around a small bag of blood in his pocket, would reach forward to pluck out Gloucester’s eye holding this hidden lychee , and then fire the bloodied ‘eyeball’ away. Sometimes it would hit the proscenium arch and stick to it. A few nights into the run Judi Dench happened to look up at the arch and saw a series of eyeballs staring down at her.

Queasy stuff. But for the audience there is no levity at all: this is sheer darkness. And yet very few students of the play react similarly to the many deaths in Shakespeare’s tragedies. Surely the defining moment in the play is the death of Cordelia, and teenagers tend not to start sniffling at that moment. Is not death worse than blinding?

But something about the nature of the eye makes this awful gouging viscerally upsetting, and also mentally disturbing. The eye is soft, vulnerable, easily hurt. The eye seems to be the primary sense in perceiving the world around us. And this scene is particularly memorable in this play because the trope ‘seeing and blindness’ is so embedded in its meaning. Pupils don’t have to see the words ‘blindness’ or ‘seeing’ in an essay title to write about these ideas: this theme is also to do with foolishness, with learning, with development, with justice and injustice.

There have already been many references to seeing and eyes in the play before, on the fifth line of the scene, Goneril says to Cornwall, Pluck out his eyes, and this is what Cornwall does, rather than the first idea, voiced by Regan, Hang him instantly. It’s clear that the former would be too swift for these three malevolent people. Just before the servants bring in Gloucester, Cornwall says, cynically but openly,

Though well we may not pass upon his life

Without the form of justice, yet our power

Shall do a court’sy to our wrath, which men

May but not control.

In other words, Gloucester needs some sort of trial (this one involves instant conviction and punishment), and Cornwall knows that no-one will be able to object (he’s wrong though: a nameless servant kills him in horror). When Gloucester arrives, Cornwall says the truly horrible line Bind fast his corky arms, and then Regan humiliates him by plucking his beard. Gloucester says that he helped the King

Because I would not see thy cruel nails

Pluck out his poor old eyes.

If they hadn’t got the idea yet, surely they do now. Then we get the double blinding, including the phrase which everyone remembers: Out, vile jelly. All is now dark and comfortless, since Gloucester cannot see in a literal sense. Then Regan reveals it was Edmund who betrayed him, and he says O my follies! Then Edgar was abused. In other words, I was stupid, I was blind. At the start of the next scene, when being guided by an old man, he tells Edgar, without knowing who he is:

I have no way and therefore want no eyes.

I stumbled when I saw.

So this scene in a visual manner encapsulates an idea which spreads throughout the story. I’m going to skip over the early parts of the play: I have already discussed the opening scene in Episode 1, in which it is obvious that Lear is blind. He is blind to Goneril and Regan’s plotting, to Kent’s true qualities, to Cordelia’s love and most of all to his own foolishness. Kent says to him See better Lear but he doesn’t want to hear, or see.

In succeeding scenes he continues to be blind, unable to accept the reality of his situation. Perhaps this is not too surprising: he has been an autocratic ruler, never challenged or questioned by his advisors and subjects. There is nothing in the position of such a man that trains him to analyse himself. Then, gradually, the weight of evidence begins to turn him: Goneril and Regan’s heartlessness and disrespect for a start. As the critic Tony Nuttall says in his book Shakespeare the Thinker,

Lear must be broken down before he is remade.

The Fool, like Kent, tries to make him see sense, see the truth, but the Fool’s many pointed comments are ignored. In Act 1 scene 5 he tells Lear that your nose is in the middle of your face

to keep one’s eyes of either side’s nose, that what a man cannot smell out, he may spy into.

But Lear fails to use either his nose or his eyes.

This theme is echoed in the sub-plot, in which Gloucester is also obviously foolish, getting both Edgar and Edmund wrong. In 1.2 he is comically inept in falling for Edmund’s trickery. When the latter pretends he is hiding a paper, Gloucester says

No? What needed then that terrible dispatch of it into your pocket? The quality of nothing hath not such need to hide itself. Let’s see. Come, if it be nothing, I shall not need spectacles.

Ironically, it is indeed nothing, and yet he does need spectacles.

The development of both these men, then, is from blindness towards some form of seeing via suffering. This might make the play seem Christian in its structure, but in fact the damage is being done now, while they are both blind. By the gouging scene, and the central storm scenes when Lear begins to see many truths, chaos has taken over their lives and will eventually destroy them. This developmental process, highly ineffectual, is also one undergone by Edgar and Albany, both decent men who eventually become clear-sighted. Again, they’re too late. Characters who can see are peripheral, ineffective or nasty: Kent, the Fool, Edmund.

At the core of the play is a series of scenes which show how Lear is changing, remaking himself and, despite his evident growing madness, become in some sense more sane. In 3.3 Lear notices the Fool’s misery – he now sees him as a human being, which he’s never done before: Come on, my boy. Art cold? and for once he responds to the Fool’s words (the rain it raineth every day): True, my good boy. In 3.4, prompted by the example of the lunatic Poor Tom, he begins to see the reality of life for many of his subjects, and 4.6 is especially important, during which he shows a philosophical understanding of the nature of justice and society which completely escaped him when he was King :

there thou mightst behold [see] the great image of authority: a dog’s obeyed in office.

He himself uses the metaphor to pointed effect:

Take that of me, my friend, who have the power to seal th’accuser’s lips. Get thee glass eyes, and like a scurvy politician, seem to see the things thou dost not.

Such ‘politicians’ see what they want to, rather than what is. He has come a long way. Earlier in the scene there is an exchange between himself and Gloucester, the two old blind men of the play:

No eyes in your head, nor no money in your purse? … You see how the world goes.

Gloucester replies I see it feelingly, which literally means that he travels by using his hands, but could metaphorically stand for the great truth of life that the play tells us: that you can only see if you feel (emotionally).

In the end, Lear’s improvement is of no use: Cordelia is killed, after he naively believed that they would be allowed to live happily ever after. At the start of that scene, Lear says to Cordelia:

Wipe thine eyes; the good years shall devour them, flesh and fell, ere they shall make us weep.

This is deluded.

Even at Cordelia’s death, Lear seems deluded as well, imagining that because the feather in his hand is shaking, it means that she is breathing. Understandably, he finds it hard to 'see' this most terrible of truths And his last lines in the play come back to the language of sight:

Pray you, undo this button. Thank you sir. Do you see this? Look on her. Look, her lips. Look there, look there.

All that suffering and remaking and improvement and humanising of Lear in the end ironically just made him all the more open and vulnerable to devastating grief.